Don McPherson ’87 was honored with the 2021 William Pearson Tolley Medal in recognition of his leadership in higher education, particularly around issues of the student experience, identity and gender violence.

His most recent platform for his work, ASPIRE, aims to create a “community of caring” leaders and learners throughout a social ecosystem that includes schools (K-12 to higher education), workplace, and families/communities.

The purpose is to establish common language and lessons that enable uncomfortable conversations, empower sustainable strategies, promote allyship and support healthy relationships. The “community of caring” encompasses and meets the needs of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), men’s violence against women and anti-racism work.

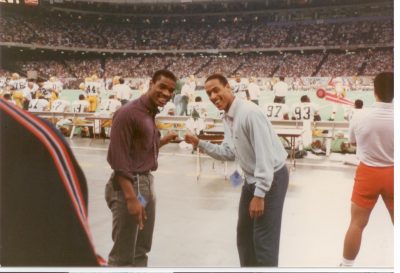

His vision of a new aspirational masculinity is based on loving, caring and vulnerable men who thrive in healthy relationships, of which his long friendship with School of Education Professor Jeffery Mangram ’88, G’09, G’06 is a prime example.

“The popular and prevailing images of masculinity have long been of stoic, physically appealing, intimidating and virile individuals,” McPherson says.

McPherson and Mangram were football teammates on the undefeated 1987 Syracuse University team: McPherson the All-America quarterback and captain, Mangram a star defensive back. They met as teammates in 1984, when Mangram was a first-year student and McPherson a sophomore.

“He was confident, and his action spoke louder than anything he said,” Mangram says of the young McPherson. “He commanded the room in which there were many guys who commanded the room. He was the alpha.”

Of their friendship nearly 40 years later, Mangram says, “We both share our vulnerabilities with each other. I think that emotional support creates a genuineness that I crave and that is so hard to experience today.”

Retiring from pro football in 1994 after playing in the NFL and Canadian Football League, McPherson shifted his focus to men’s violence against women. Joining Northeastern University’s Center for the Study of Sport in Society, he became director of its Mentors in Violence Prevention Program in 1995, taking over for the program’s founder, Jackson Katz.

At 29—as he wrote in his book You Throw Like a Girl: The Blind Spot of Masculinity (Akashic Books, 2019)—he realized how he had mastered performing the popular image of masculinity. “I had delayed the inevitable—that moment every man faces, when he realizes he didn’t say, ‘I love you’ enough or put away his pride more and hug those he cared about, living in the unashamed and vulnerable wholeness.”

A new Don McPherson emerged. “Once extricated from that culture and immersed in the work, my voice was very natural and freeing, as I like to say, freed by feminism,” he says.

He’s visited more than 350 college campuses, community organizations and national sports and violence prevention organizations to conduct workshops and lectures for more than 1 million people. From these experiences, he formulated ASPIRE that recognizes a social ecosystem in which higher education sits in the center.

McPherson calls this portion of ASPIRE “Recruitment to Employment,” a strategy proposing that such work on social issues is the responsibility of all departments and offices on campus from how students are attracted to campus, to how they are prepared for what he refers to as the “DEI Economy.”

It’s a topic he and Mangram have discussed often.

“Donnie believes that if higher education institutions insist on and continue to build on the work pre-K educational institutions began around character and their virtues, SU graduates, for instance, will be better prepared for workplace issues such as sexism, racism, intolerance, theft and the like,” says Mangram.

Lessons from sports apply in ASPIRE and in stopping men’s violence against women. McPherson wants to emphasize excellence, not scare tactics in what he calls the heat of the moment—the test, the game, the time that reveals preparation and character.

“In the classroom, in sports, in theater, we prepare for the heat of the moment with sound, positive principals and strategies. When it comes to social issues, the uncomfortable conversations are replaced with prevention language and scare tactics,” McPherson says. “We prepare for challenges in the classroom by teaching and nurturing excellence. Aspire is designed to be aspirational and focused on teaching excellence, as opposed to prevention.”

Mangram concurs: “I agree with Donnie from this standpoint: College graduates need to be consciously taught skills in which to engage a multicultural world in which change is ever-present. It is about being proactive instead of reactive.”

Note that the professor calls his former teammate “Donnie.”

As McPherson explained in his book, most athletes are known by three names: their given name, which family and close friends use; their media name, which fans use; “and the name their teammates call them that signifies camaraderie, affection and style … that fellowship that made football the game I loved.”

For McPherson, those three names, in order, are Donald, Don McPherson and Donnie Mac.

He describes how his friendship with Mangram developed after “we were thrust into the involuntary relationships within the football team that required us to learn how to work together before we actually knew each other.” Players tended to gravitate to those who made them feel comfortable on the surface.

“But Jeff rarely just engaged on the surface. He was intensely curious and an enthusiastic learner. Though we shared a lot in common regarding football, we were from different worlds. Brunswick, Georgia, is a long way from Long Island.”

Mangram came to Syracuse from Brunswick, a city of 15,000 on the Georgia sea coast in a county of nearly 60,000. McPherson, son of a New York City police detective, grew up on suburban Long Island.

“We bonded in learning about each other in very robust conversations,” says McPherson.

They agree their friendship endures because of their expressed love for each other.

“We share the ebbs and flows of our existence, with a lot of laughter sprinkled in there,” Mangram says. “We tell each other that we love each other, and that sustains me until we talk again.”

That love flows, McPherson says, from how successful organizations learn to manage involuntary relationships, such as that undefeated Orange football team. “Nowhere is this more transparent than in sports. Successful teams are those where individuals learn to love and trust one another. It creates special bonds that are lifelong and intimate.”

“You Throw Like a Girl” has been the title of McPherson’s college campus lectures since 1996. Originally presented as the language of sports, it quickly became the term for understanding narrow masculinity and misogyny. It is a prominent scene from a 1993 movie, The Sandlot, about the love of nine California boys for baseball in 1962, in which “You play ball like a girl” is one of the memorable lines. “As an insult, it is arguably one of the most aggressive assaults on the psyche of boys and men,” he wrote in his book.

It’s also an ironic title. In teaching boys and girls how to throw a football, he wrote, boys are always initially harder to teach, since they think they already know how. Girls listen and apply what he tells them in the right order. “In every one of those cases, to ‘throw like a girl’ meant throwing the proper way,” he wrote.

Students are active participants in his lectures, McPherson says. Adults need to approach them on the students’ level, matching wisdom with awareness in presentations.

“Society is evolving rapidly, and while students are aware and hungry for dialogue, many adults are unwilling or incapable of engaging in uncomfortable, nontraditional discourse,” he says. “The strength of my work has always been the ability to make complex issues and content relevant and accessible. To that end, I have found students always highly engaged in the conversation.”

What McPherson calls “ aspirational masculinity” is “deliberate, intentional, loving, caring, egalitarian and nonviolent.” In his book he wrote, “It’s time for us as men to expand the definition of what it means to be men, understand the complexities of our gender, and learn to be loving, caring and whole as we raise the next generation of boys to be loving, caring and whole.”

His father exemplified, but never articulated, those qualities. “My father was hardworking, tough and stoic—an old-school dad,” he wrote.

So it was vital to the growing friendship of the two football players when Mangram visited the McPherson home and displayed his curiosity and thirst for learning.

“Some of my favorite memories of Jeff are sitting at the kitchen table in my childhood home on Long Island grilling my father with questions about the job” of a police detective, McPherson says.

“He asked my father questions we, his children, never asked and was genuinely fascinated by the opportunity to talk with him. I’m not sure who appreciated that more, my dad, Jeff or me.”

From those experiences grew McPherson’s new vision of a healthy masculinity that he has taught to students for decades, a journey that brought him to this year’s Tolley Medal.