With nearly half (46%) of US teens ages 13 to 17 reporting being targets of cyberbullying—according to a 2022 Pew Research Center survey—instructional design master’s degree students Tavish Van Skoik G’24 and Jiayu “J.J.” Jiang G’24 have developed a process to help school districts address electronic aggression, reported by survey respondents as a top concern for people in their age group.

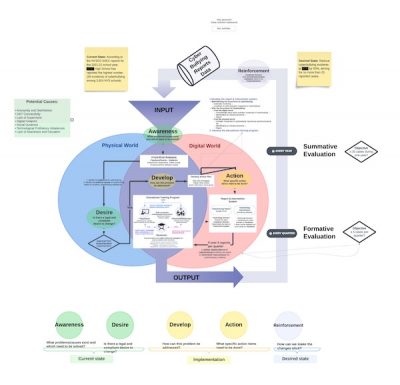

Van Skoik and Jiang created “Cyberguard,” an anti-cyberbullying model, for their final project in Syracuse University School of Education’s IDE 632: Instructional Design and Development II. This course requires students to develop an instructional design model and appropriate, accompanying implementation documentation.

Particularly Vulnerable

Van Skoik’s and Jiang’s model proposes a process for educational institutions to follow that should help to reduce the number of cyberbullying incidents. Currently, it is under review with EDUCAUSE, with hopes to be published soon in the higher education technology journal and presented at its annual conference in November 2024.

Having taught middle school for six years, and later working as an instructional technology specialist for a school district in South Carolina, Van Skoik saw both the effects of student cyberbullying play out daily in his classroom and how his district tracked students’ use of school-issued computers. His firsthand experience sparked the idea for the model.

“I think middle schoolers are particularly vulnerable as far as emotional intelligence, behavior modification, and behavior management are concerned,” says Van Skoik, who believes the model’s interventions implemented at this age would help students learn as they grow. “Then by the time they’re in high school, which this data is from, there would be a reduction in cyber bullying cases.”

The pair used the New York State Education Department’s School Safety and Educational Climate (NYSED SSEC) incident data to identify the state high school with the highest number of self-reported cyberbullying cases in the state. That school—which the pair are not disclosing—was then used as the focus of their model. The school reported 39 cyberbullying incidents over the 2021-2022 school year, which the pair says is a high figure compared to other schools’ average of 0.67 incidents per school.

Based on this data, the pair devised their model as steps school districts can follow to reduce incidents. The model, they say, acts as a positive feedback loop by raising awareness, identifying cyberbullying, and preventing further cases. “The point of the model is the awareness of what cyberbullying is,” stresses Van Skoik, who says by bringing the issue to students’ attention, attitudes can be changed and good behavior reinforced as the process is evaluated each school quarter.

When Both Worlds Meet

The Pew survey found that teens use six cyberbullying behaviors: offensive name-calling (most reported), spreading false rumors, receiving explicit images, physical threats, harassment, and having explicit images of them shared without their consent.

Online anonymity, 24/7 connectivity, lack of supervision, and digital footprints—traces of online activity that can be used to provoke cyberbulling—are among the causes of electronic aggression that the pair identified. “If we can address those potential causes, J.J. and I believe the cases will come down,” Van Skoik says.

Regarding online anonymity, too often people can hide behind a screen, creating a persona that often says or does things a person would never do if face to face. “This model eliminates that possibility,” Van Skoik says. “It has to bridge the gap because the educational training program is the only thing that can happen when both worlds meet.” The model brings these two worlds—digital and real—together by emphasizing the importance of a holistic approach that combines data-driven interventions, educational training programs, and repetitive assessment.

The pair suggest interventions take place in both the digital and real worlds. First, they recommend schools develop an automatic monitoring system by installing software on devices the school loans out.

They note that monitoring is helpful to the entire school community and not only to students because teacher and administrator computers can be monitored to identify any incidents among staff as well. According to the Pew survey, three in 10 teens say school districts monitoring students’ social media activity for bullying or harassment would help.

Software can record and report suspected incidents of cyberbullying, and Jiang suggests AI also could be used in the monitoring program. “A lot of students hide bullying action in the cyberworld,” she explains. “AI can recognize and also learn how to make a decision about if there is a risk of cyberbullying or not?”

For in-person intervention, the pair recommends schools collect feedback from students, staff, and parents at the beginning of the school year to have a baseline assessment. This can include mental health evaluations when recommended.

Next, an educational training should be implemented during teachers’ professional development sessions, as well as for students and parents. Finally, an avenue to allow staff, students, and parents to report incidents of cyberbullying should be created, and all interventions should be reviewed quarterly to track incidents, to see if there is progress or if the process needs to be refined.

Why We’re Not Learning

Both Van Skoik and Jiang strongly believe that in addition to use of monitoring software, schools must provide training and education about online social behavior. “School’s goal is to learn, that’s why we’re in this environment,” says Van Skoik, who often saw cyberbullying interrupt lessons in his classroom. “So, if we can’t learn, we have to find out why we’re not learning.”

Today, he says, society—and schools—are impacted by so many devices causing distractions, and in some cases, harm.

The educational training that the pair recommends can be offered in multiple ways, such as an online training, in-person session, or mixture of both. “The ultimate goal is for the educational training program to address the issue that there is a cyberbullying concern at the school, and—I think—it’s another way to create awareness,” Van Skoik notes.

A final goal of Cyberguard is to create a culture of reporting online harassment. While software can help to identify suspected incidents—based on keywords, for example—avenues for self-reporting can also be implemented, either by having students, staff, and parents complete a Google form or by encouraging students to raise concerns to guidance counselors and school staff.

“I hope this model can improve everyone’s awareness and help them develop skills on how to report cyberbullying,” Jiang says.

Ultimately, the Cyberguard model serves as a template for schools and, Jiang says, it will evolve after initial implementation. “In the first year, formative evaluations will be conducted every quarter to test our objective,” she explains. If incidents of cyberbullying decline, the objective is met.

In year two, objectives can change, with a goal of seeing greater declines. Across years three to five, the pair will evaluate the model’s effectiveness by comparing the number of cases each year, hoping to see a stark decline.

“Our theory is that the prevalence of cyberbullying results from a lack of awareness, education, and training,” Van Skoik concludes. “This is what instructional design tells us—it comes from a lack of knowledge, skills, and attitudes.”

By Ashley Kang ’04, G’11 (a proud alumna of the M.S. in Higher Education program)

Learn more about the master’s degree in Instructional Design, Development, and Evaluation (with a fully online option), or contact SOE Graduate Admissions at soeadmissions@syr.edu.