It’s officially called the Summer Literacy Clinic, but there’s much more to it than one-on-one reading and tutoring.

True, when you enter the library of Roberts PreK-8 School in the Syracuse City School District (SCSD), you see third- and fourth-grade students sitting at the low tables with graduate students. But in addition to picture books, there are computers, notebooks, and even drawing paper. The children are allowed to take breaks in the adjoining playground, and colorful, hand-drawn posters adorn the walls.

It might be more appropriate to call this a “literacy camp,” muses Syracuse University School of Education Professor Bong Gee Jang, who oversees the clinic and the master’s degree students gaining experience in it.

Reinforce the Lessons

Why a “camp” and not a “clinic”? For one, it uses a community-based model rather than a commercial or medical one. That is, instead of parents paying tuition and board to send their children on to SU campus for reading intervention, this program is part of Roberts’ Summer School activities. Students take other classes during the day and receive free breakfast and lunch.

Secondly, rather than relying solely on phonics and decoding, the summer program “is an intermediate, asset- and inquiry-based program focused not only on comprehension but also digital reading, writing, and research skills,” explains Jang.

The program offers two sessions a day across three weeks in late summer. In the first session, third and fourth graders are encouraged to research a topic that interests them, guided by the graduate students toward a creative synthesis of material through a process of reading, analysis, and synthesis of printed materials and age-appropriate internet research. This approach adheres to state and national literacy standards, says Jang.

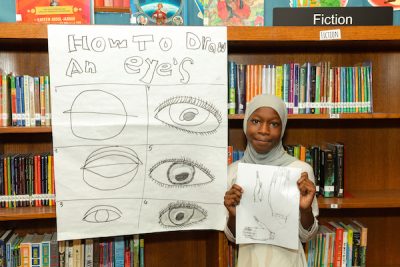

The first session culminates in early August with the students presenting what they have learned in front of their peers, using PowerPoint, posters, or even video and podcasts. “Publishing is important for literacy learning,” notes Jang. “Sharing what is read and discussed helps reinforce the lessons and strengthen social interactions.”

Gaining Independence

The graduate students are working toward an M.S. in Literacy Education (Birth-Grade 12), which leads to initial and professional New York State teacher certification in literacy education (Birth to Grade 6 and Grades 5 to 12). The summer clinic is the final course of a one-year, three-semester program (there is also a two-year, part-time option).

“Because this is a student-centered, inquiry-based program, the teachers must do a lot of work, with thorough planning and implementation of reading and writing strategies.”

—Professor Bong Gee Jang

“Because this is a student-centered, inquiry-based program, the teachers must do a lot of work, with thorough planning and implementation of reading and writing strategies, to help students gain independence,” observes Jang, adding that many of the graduates will go on to become literacy coaches or interventionists.

After the early morning session ends, around 10:30 a.m., it is the turn of seventh and eighth graders. The second session offers a different tutoring model, again overseen by Jang and his assistants, Ibrahim Kizil, a Literacy Education doctoral candidate, and alumni Kaitlyn Ertl G’21, a third grade teacher at Chestnut Hill Elementary in the Liverpool Central School District, and Midheta Mujak G’21, an English as a New Language (ENL) teacher at Nottingham High School (SCSD).

Like the younger children, these older students are still guided in reading and research, but this time two graduate students sit at the table with them: one is the trainee tutor and the other is the tutor’s peer observer/coach. “Team teaching is part of the state standards to be a literacy coach,” explains Jang. “Literacy coaches need to know how to collaborate and coach other teachers.”

Self-Motivated

“I like working closely with my peer coach. She helps me to grow,” says Tuyet Nguyen, who graduated from the literacy master’s degree program in August 2023, after the Summer Literacy Clinic wrapped up. “In my school, I only get observed twice a year.”

An ENL tutor at H.W. Smith Pre-K-8 School (SCSD), Nguyen says she chose the program so she could help her students learn to read. “Many of them speak fluent English, but they can’t read,” she continues, explaining that her undergraduate degree in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages emphasized decoding language rather than literacy.

The SOE graduate degree, she says, compliments her knowledge as well as her original certification, for teaching kindergarten through 12th grade. Moreover, the program’s inquiry-based approach compliments her understanding of literacy as “not just about language but also about understanding content.”

In the morning session, Nguyen tutors Maria. Born outside the US, Maria is a bright fourth grade ENL student and a budding artist whose research interest is how to draw hands and eyes. Nugyen says she immediately connected with Maria because she too was born in another country—Vietnam—and didn’t learn to speak or read English fluently until after she immigrated, at age 10.

“Maria speaks a different language at home, and she has learned to read by memorization rather than decoding,” observes Nguyen. “Like other kids, she needs breaks and benefits from different approaches, but she is very enthusiastic and energetic. She’s self-motivated.”

Shy at first, by the end of the three-week session, Nguyen says she and Maria were joking together. One particular student-centered research technique seemed to work well. “When she asked a question about her research, I pretended not to know,” explains Nguyen. “Maria said, ‘But you’re the teacher!’ She can be afraid to make mistakes, but instead of telling her the answer, we researched together so that I could direct her toward it. That took the pressure off her.”

Although posters of Maria’s research and practice drawings are taped on the walls, for her final presentation she chose PowerPoint slides. “She did great,” says Nguyen. “Maria is growing as a student in her own way. She’s becoming more confident.”

Really Wonderful

Jang notes that the Summer Literacy Clinic is one of several community-based literary services offered by the School of Education. It is joined by Writing Our Lives at Elmcrest Children’s Center, a literacy and creativity program that empowers youth to share their stories, developed by Associate Provost Marcelle Haddix, and the Breedlove Readers Book Club, directed by Professor Courtney Mauldin. Another program is SOE’s Spring Reading Clinic, which offers explicit, phonics-based literacy intervention using the Road to Reading program.

Jang praises SCSD’s literacy partnership with the School and University—“They have really been wonderful in supporting us”—citing a July 2023 Literacy Summit as another example of how the SCSD and University are working together to improve reading in the district and train diverse literacy coaches.

Led by Haddix at The Nancy Cantor Warehouse, the summit featured SOE Dean Kelly Chandler-Olcott and Mauldin, who discussed SOE’s literacy initiatives. Also speaking were SCSD representatives (presenting on the “Landscape of Literacy Education in Syracuse”) and SU’s Shaw Center for Community Engagement Literacy Tutoring Corps. Part of America Reads, the Corps sends more than 200 reading tutors into the community each year.