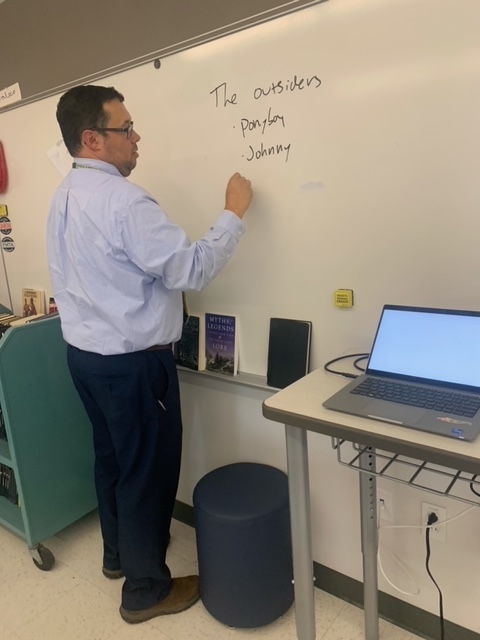

“Zero,” answers middle school teacher Aaron Dorsey G’03, G’17, to the question: “As a student, how many Indigenous teachers have you had?”

Over his entire educational career—kindergarten to master’s degree—he says there was almost no one of color standing at the helm.

“In all of that time, maybe one or two of the teachers I interacted with were culturally diverse,” says Dorsey, a graduate of Syracuse University School of Education’s master’s in English Education and Educational Technology certificate programs. “I had very little contact with anybody Native, even at the college and graduate levels, and I think that’s unfortunate.”

Now, thanks to an anonymous benefactor, $150,000 has been provided to SOE to boost the pool of Indigenous educators. The Indigenous Teacher Preparation Fund will provide scholarships to at least seven undergraduate students in its first cohort, which will matriculate by the 2026-2027 academic year.

Much of teaching benefits from the unique perspective a teacher brings, says Dorsey, who currently serves as English Department Chair and an eighth-grade teacher at Wellwood Middle School in the Fayetteville-Manlius (NY) School District, near Syracuse: “Native teachers can create a curriculum that’s culturally responsive, so their culture bleeds into what they’re doing in the classroom. Their presence creates a welcoming and affirming environment for Native students.”

“One thing that is very clear to me as a teacher is the lack of educators with Indigenous cultural heritage,” Dorsey continues. “It causes a dilemma, because we have nation schools—such as the Onondaga Nation School in Lafayette, NY—and many throughout the country. But the reality is, because there aren’t a lot of people of Indigenous background becoming teachers, those children are not seeing themselves reflected in their educators.”

He adds: “It’s nice to see people who look like you, in stories you read, on TV, and especially in the classroom.”

Moving Forward

Historically, forced relocation, genocide, and the abduction of youth to more than 350 US government-funded boarding schools created a shared sense of trauma among Indigenous communities. That mistrust still remains—with one result being a lack of Indigenous teachers.

“I felt a lot of community and collectivity with all the Native services provided. Syracuse was home away from home.”

Kelsey Dayle John ’16, G’19

Education schools, believes Heather Watts G’12, a former Haudenosaunee Promise scholar, have an obligation to educate about these legacies.

“Teacher candidates need to understand how this trauma may show up in Indigenous communities,” explains Watts, Mohawk from Six Nations of the Grand River Territory. “Grandparents, and even parents, may have experienced life in a boarding school, and they may have total mistrust for the education system.”

This apprehension may prevent guardians from visiting their children’s schools, which may be misinterpreted as a lack of care for their education. This mistrust may trickle down through generations, making Indigenous children view schools as unsafe spaces. Boarding schools also fostered a sense of “othering” of Indigenous peoples.

Today, Watts leads Canada-based consulting firm First Peoples Group, advocating for more Indigenous teachers to address educational gaps. She taught at various charter schools in New York State after graduating from SOE with a degree in inclusive education, before pursuing graduate degrees on education policy. Currently, she is focusing her doctoral research on Indigenous reclamation of education systems.

Watts stresses that teachers must know how education has been used to perpetuate harm against Indigenous peoples and then “consider how education can be used as a vessel for healing, moving forward, and centering Indigenous knowledge.”

Watts suggests that SOE might forge a deeper relationship with the Onondaga Nation School—located less than 15 miles from campus—where she completed a placement: “It was incredible to think about the principles of inclusive education, which I so valued learning at Syracuse, and how that could be fostered at Onondaga Nation School. These principles of inclusion are very much echoed in Haudenosaunee ways of knowing.”

While her mentor teacher was non-Indigenous, Watts says the educator nevertheless knew when to seek guidance from Indigenous colleagues: “She included me in decisions around curriculum or on best practices for communicating with parents and families.”

Watts says she’s excited to see the journey the recipients of the Indigenous Teacher Preparation Fund will take. “It’s very much needed, especially in New York State,” she adds. “I hope SOE keenly listens to students’ suggestions on how programming and content can be improved. While SOE has so much to offer in terms of training future educators, it too is in a position to learn from Indigenous communities.”

Great Opportunity

Not only are more Indigenous teachers needed, but so are more school leaders, administrators, and even school board members, says Hugh Burnam G’23, Mohawk, Wolf Clan.

“While SOE has so much to offer in terms of training future educators, it too is in a position to learn from Indigenous communities.”

Heather Watts G’12

A graduate of SOE’s Cultural Foundations of Education doctoral program, Burnam specializes in Indigenous sovereignty in education and currently works at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center to support STEAM programs. He is also Co-chair of the Native American Indian Education Association of New York State and teaches SOE’s “Indigenous Knowledge, Identity, and Learning” online summer course, cross listed with the College of Arts and Science’s Minor in Native American and Indigenous Studies.

“You’re even less likely to find administrators who are Indigenous,” Burnam observes. “Those are key decision makers.” He believes the Indigenous Teacher Preparation Fund will help create leadership pathways: “It’s a great opportunity, and I would like to see Syracuse continue it into the future.”

In addition to the undergraduate scholarship, Burnam notes that greater opportunities for Indigenous student teachers to move into master’s and doctoral degrees—not to mention expanded experiential learning options—”would be really important to continue that pipeline.”

Community and Collectivity

The new scholarship fund creates a double investment, says Kelsey Dayle John ’16, G’19: “It shows not only that Syracuse values teachers but that we value culturally relevant teachers. When you value something, you put resources toward it, showing that you’re valuing what you’re describing and not just saying it.”

Hailing from the Southwest, Syracuse offered John, who is Diné, a totally different experience than she had growing up in Oklahoma: “I felt a lot of community and collectivity with all the Native services provided. Syracuse was home away from home.”

Holding a Certificate of Advanced Study in Women’s and Gender Studies and a Ph.D. in Cultural Foundations of Education, John found that SOE encouraged of diverse ways of knowing: “My program was so supportive with me and the research path I wanted. If they didn’t have a resource I needed, they helped me find it.”

John says she was even able to complete classes at different universities that fit her research focus on Indigenous animal studies, such as an Indigenous philosophy class at Cornell University with an Indigenous professor.

Looking back, John thinks it would have been powerful to have an Indigenous teacher earlier than college. “The amount of microaggressions and subtle forms of anti-Indianness that I experienced throughout my K-12 education was prolific,” she says. “Having my first Indigenous professor at 19 was life changing. If Native students could experience that life-changing moment earlier, that’s an amazing thing.”

Cultural Steward

Dorsey, who carries Indigenous blood through his father’s side, holds no official tribal affiliation. His late father was a member of Onondaga Nation through his mother and, through his father, he was Lenni Lenape (Delaware). “I’m half Native, but it’s through my dad, so unfortunately, I cannot obtain tribal affiliation.”

Looking back, Dorsey says his childhood was mostly devoid of Indigenous culture: “My dad was estranged from his family due to really unfortunate circumstances. And I think he never really wanted to teach me that I’m a Native person, because for him, that meant pain.”

It’s that pain, he believes, that later fueled his desire to be someone who identifies as Indigenous and learn about his culture.

He feels that many Indigenous people experience cultural trauma. “That means having someone who can empathize with that cultural perspective is very important for Native children in an education setting,” he says. “My dad was not necessarily ashamed to be Native. Instead, he carried the cultural trauma and lived it from day to day.”

As an English teacher, Dorsey says he uses books as “windows and mirrors,” allowing young readers a chance to look into someone else’s experience or reflect on one’s life similar to their own.

With hope, Dorsey sees a new wave in education, one working to embrace cultural appreciation and understanding: “To me, the importance of having culturally diverse educators is that they themselves can model and embody the culture which allows students to both see themselves, and also grow empathy for other cultures.”

In his roles at Wellwood Middle School, Dorsey describes himself as a cultural steward. “It’s important for me to foster empathy,” he says, “and I think it’s great that through this new School of Education scholarship, an authentic voice of what it means to be a Native person will expand into the classroom.”

By Ashley Kang ’04, G’11 (a proud alumna of the M.S. in Higher Education program)

To inquire about scholarships through the School of Education Indigenous Teacher Preparation Fund, contact Tammy Bluewolf-Kennedy at tbluewol@syr.edu. Contact the School of Education to learn more about its teacher preparation programs.