Scaling Up: Syracuse Expands Learning Simulations

Clinical simulations give students a hands-on, safe learning environment to engage in interactions with a trained actor. Syracuse University just added to its 60-plus simulations with a new financial ethics simulation.

(Inside Higher Ed | April 6, 2023) One educator at Syracuse University is propelling real-world learning with clinical simulations to teach undergraduates how to navigate tense, awkward, unfamiliar or ethically fraught conversations in their careers.

For over 15 years, the School of Education has utilized simulations in its curriculum, establishing engaging, shared learning environments in a low-risk setting and prompting students to participate in data-based reflection and strategizing.

Whether it’s de-escalating an angry parent, addressing plagiarism in the classroom or counseling children through abuse or divorce, Syracuse students practice holding difficult conversations and learn best practices for the future.

Syracuse University’s Center for Experiential Pedagogy and Practice, which opened in March 2022, launched its first business-oriented experiential learning simulation at the end of March for students at the Whitman School of Management.

What’s a sitch?

A simulation, as defined by Ben Dotger, education professor and director of the Center for Experiential Pedagogy and Practice at Syracuse, is a manufactured live interaction that is recorded and takes place person-to-person with specific learning objectives.

The essential factors are “person-to-person” and “live interactions,” Dotger explains, because it differentiates the experience from a role play or a rehearsed dialogue between students.

Sims are most typically used in a clinical or medical settings to train future physicians, nurses, physical therapists or similar role to practice diagnostics or communicating with a patient.

“We try to bring to life the most common situations, the most frequent or prevalent, and we try to bring to life those that are less common but that we really need our professionals to be on point when they encounter those less common situations,” Dotger says.

A common example for a future educator may be communicating with a proactive parent who has a few questions about curriculum, whereas something less common but critical to understand is a parent who wants to remove a book from the classroom.

Syracuse’s SIMS

Dotger began incorporating sims into his curriculum in 2007, partnering with SUNY Upstate Medical University and its Clinical Skills Center to use their trained actors, who served as standardized patients in simulations, to become standardized parents, colleagues or students for Syracuse.

“We try to bring to life the most common situations, the most frequent or prevalent, and we try to bring to life those that are less common but that we really need our professionals to be on point.”

—Professor Ben Dotger

Syracuse’s the initial simulations were for educator preparation—teacher education, school leader education, school counseling, etc.—but have expanded to creative arts therapy and, most recently, business and marketing students. The university also offers simulations for veterans exiting the military and returning to campus life, with a grand total of 64 different sims.

In his course Early Foundations, Dotger’s students complete six simulations over a 15-week semester.

How It Works

The simulation experience can be broken down into six phases.

The student receives a learner protocol, which comes with a “reasonable amount of information,” three to five days before the scheduled simulation, Dotger says. “That sounds a little vague, and I mean it to be a bit vague.” Sometimes, a simulation is a scheduled meeting or interaction that the student will lead with the standardized parent. Other simulations are more off-the-cuff.

“As educators, we will have interactions with parents or colleagues, sometimes on a Saturday morning in a grocery store parking lot, sometimes late afternoon in a school hallway,” Dotger explains. “We didn’t initiate the conversation; we’re not really sure what the person may be concerned about or might want to ask us. So sometimes the situations we put them in are intentionally pretty vague. The expectation remains the same: do your best.”

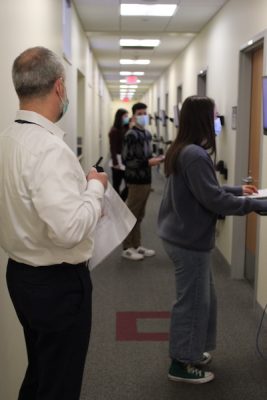

Then, it’s the day of the simulation. The interactions take place in an isolated room with cameras recording the entire process, which lasts around 20 minutes. Students will cycle through in a few groups of four to five simultaneous simulations.

Following the interaction, students have an immediate 10-minute group debrief with their instructor.

Then, students rewatch the simulation, reviewing what went well and what could be improved.

The next time the class meets, a few students will show their simulation footage and point out clips that demonstrate both what the student was proud of or what could be learned from. Dotger says students typically dissect about 50-50 positive versus negative feedback of their own simulations.

“My job in class is really just facilitating that whole group debrief to make sure we cover the range of issues within that given sim,” Dotger adds.

Finally, students turn in a reflection paper, time-stamping examples of their simulation successes and areas of improvement …