“Growth” and “perspective” are the top gains Syracuse University School of Education (SOE) alumni note when reflecting on a semester spent student teaching in New York City.

While the Bridge to the City program is an accelerated immersive experience—two placements in the fall semester, lasting six to seven weeks each—former students say their time putting inclusive teaching theory into practice allows them to see themselves transforming into a teacher.

“Bridge to the City is a great opportunity for our students to really find their teacher voice,” says Christy Ashby G’01, G’07, G’08, Professor of Inclusive Special Education and Disability Studies and Director of the Center on Disability and Inclusion, who is completing research on student experiences in the program.

Selling Point

Ashby, who was a graduate student at Syracuse University when Bridge to the City launched in 2003, has taught students in the program over the last decade and has witnessed its growth. “This opportunity to student-teach in New York City is really unusual amongst our peer institutions,” she says. “It’s become a real selling point for the school.”

“This opportunity to student-teach in New York City is really unusual amongst our peer institutions. It’s become a real selling point for the school.”

Professor Christy Ashby

Thanks to its two-decades-long commitment to providing an inclusive education placement experience through guided mentorship, the program has become a cornerstone of the University’s study away offerings in New York City.

It also has transformed the lives and careers of generations of educators. “We have this genealogy of students that have graduated from our program, gone down to New York City, and stayed,” Ashby says.

Ashby’s research on student experiences from the program is aided by Emilee Baker, an SOE doctoral candidate. The pair spent a year and a half interviewing alumni of the program for a forthcoming paper. Respondents all noted significant personal and professional growth.

“The next section of the research will go deeper into the alumni network of Bridge to the City,” Baker notes. It will examine teacher retention rates, asking “Does Bridge to the City equate that you’re going to be more successful as a teacher long term?”

Something New

“A Bridge to The City” was the title of a program development proposal put forward by Professor Emeritus Gerald Mager, who taught courses on inclusive classrooms. Receiving a 2001 Laura J. and L. Douglas Meredith Professorship gave Mager three years of funding to support his idea. The proposal called for development of a two-way partnership between the University and New York City schools to provide SOE students a semester of guided student teaching in an urban setting.

In the late 1990s, Mager played a pivotal role in developing an inclusion program, a groundbreaking approach for general education classrooms where students with and without learning differences learn together. This experience prompted him to extend this model to New York City, a place in need of qualified inclusive educators. “Although they have many teacher preparation programs in New York City, none were overly inclusive at that time,” Mager observes. “This was going to be something a little bit new for city public schools.”

“My proposal was to build out connections and launch the program based on my background and my commitment to teacher preparation,” Mager recalls. He spent the first year establishing partnerships; the second year connecting SU faculty to schools and staff in New York City, as well as bringing administrators from city schools to SU; and by the third year, the first group of SU students were exploring inclusive teaching practices in schools across the metropolis.

“I think what really surprised me during the Bridge to the City program were the amount of children that really relied on us to be a secondary parent figure.”

Sarah Stumpf ’00, G’03

The Meredith Professorship and Mager’s efforts set the stage to develop a network of support to grow both the program and cultivate a pool of future educators. That network remains to this day. “If I hadn’t had that Meredith project,” he says, “it just wouldn’t have happened because there were no resources for it.”

The initial proposal gained momentum with support from Professor Corinne Roth Smith, who served as SOE Interim Dean from 2000 to 2002. Having leadership and other faculty behind the initiative, Mager says, led to backing from University administration, which propelled the program forward.

Mager says his vision for the project was never for it to be under his direction, but for it to become an established and supported offering for SOE students and partner schools: “If it was my project only, it wasn’t going to be any good. It could only work and be sustained if other people began to be involved in it and to own it.”

Support Network

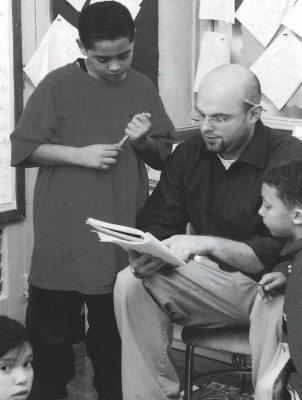

Bridge to the City students teach full-time—with mentored guidance from professors and seasoned teachers—honing skills in both general and special education. Additionally, they participate in seminars reflecting the work they are doing in the field.

“Faculty both teach and supervise,” Ashby explains. “Thus, students get the freedom and independence of experiencing teaching in a new city, but with the safety net of their school colleagues and their faculty supporting them.”

One participant from the 2003 pilot class, Sarah Stumpf ’00, G’03, says the program solidified her commitment to teaching and shaped her understanding of the broader role educators play in students’ lives.

“It was an amazing experience,” says Stumpf, who remembers she was one of six students participating that fall. The program starts the day after Labor Day, launching with a session on professional development, and then wraps up around Thanksgiving. Students live in the city with their peers, helping to establish a dedicated support network.

“As a cohort, we made sure we ate together at least once a week,” she says. “My roommate and I would proofread each other’s lesson plans. We really made sure that we kept an eye on one another. We made sure everyone was safe, eating, and being supported—not just by Professor Mager but by one another.”

Stumpf’s journey is emblematic of the program’s broader goals, to instill a sense of responsibility as well as a commitment to inclusion and social justice in future educators.

Intentionally Diverse

New York City is a unique microcosm of education, doctoral candidate Emilee Baker explains, not only in its diversity of students but also because so many different school networks are operating.

“The schools we place our students in are not random,” Professor Ashby adds. “These are schools that are intentionally diverse.” This deliberate choice, she says, exposes students to various models of instruction and ensures that they learn to navigate the reality of inclusive education in action.

The program’s success is not only measured by the impact on students but also by its contribution to equity and justice in the broader educational landscape.

“I think what really surprised me during Bridge to the City were the number of children who really relied on us to be a secondary parent figure,” Stumpf reflects. “There were quite a few days where teaching was secondary. Making sure that my students were fed, bathed, had clean clothing, or they had things to write with came first.”

“Critical reflection is part of what we do,” explains Tom Bull, Director of Field Relations for the program. “We have students reflect on what they’ve learned and experienced, and it is pretty consistent in terms of theme.”

In his near decade leading the program, Bull says he has watched students arrive anxious about leading a class and navigating a new city, but in the end the growth they achieve consistently exceeds expectation. “The program provides a scaffolded, progressive structure,” something that Bull says is one of its greatest strengths, setting up students for success.

As Bridge to the City celebrates its 20th anniversary, the program’s ability to evolve, adapt, and consistently produce educators equipped to navigate the complex landscape of urban education speaks volumes about its significance.

And as the program looks toward the future, there is a collective hope that it will continue to shape educators for years to come. “I’m thrilled it’s been going for 20 years,” Ashby says. “I hope it’s going for 20 more.”

By Ashley Kang ’04, G’11 (a proud alumna of the M.S. in Higher Education program)

Learn more about the Bridge to the City program or contact Professor Christy Ashby.