Since 2008, the Upstate Medical University Life Sciences exhibit at Syracuse’s Museum of Science and Technology (MOST) has fascinated millions of visitors. Thanks to giant reproductions of human body parts, it allows mini pathologists to explore internal anatomy and organs common to all humans.

But its depiction of one organ—the skin—was not as encompassing as it could be.

Now, the MOST’s body exhibit has received a much-needed inclusive make-over, thanks to a Syracuse University School of Education arts education professor and his former student.

Preserving Art

For close to 30 years, Karyn Meyer-Berthel G’21 has worked as a professional artist, becoming known for her ability to combine paint colors into perfect matches to any skin tone.

This skill, she says, came over time. Her start was painting theater sets.

For theater, she painted backdrops and scenery, primarily for opera and musicals. “Musical theater was my favorite to paint because it was usually really dramatic and full of character,” Meyer-Berthel says, who had to stop after an injury. “That kind of work is heavy labor—you’re carrying five-gallon buckets of paint; you’re standing on your feet all day. I loved it, but having that injury, I had to give it up. So that led to a world of figuring out all these different jobs in the arts.”

A slew of roles followed, including working for three different art material manufacturers, as well as a year as a Mellon intern, where she assisted in the conservation department at the National Gallery of Art.

“The work I did there was on painting conservation and understanding what materials last a really long time,” Meyer-Berthel explains. She learned not only how to preserve art for future generations but also how museums can protect pieces from the public, learning which materials work best to seal historic treasures, especially from the oils on little fingers that crave to touch them.

According to her former arts education teacher, this notable professional background combined with her art materials expertise made her a perfect fit to help complete a needed update to the MOST’s human body exhibit.

Professor James Haywood Rolling Jr.—who has taught arts education at Syracuse since 2007, serves as Interim Chair of the Department of African American Studies, and is a dual professor in the College of Visual and Performing Arts and an associated professor in the College of Arts and Sciences—also runs JHRolling Arts, Education, Leadership Strategies. In his role as consultant, he was tapped to help the MOST make improvements to its exhibits, with an eye toward equity and inclusion.

“That Life Science exhibit was over 10 years old, and it’s striking that there were no persons of color represented.”

Professor James H. Rolling Jr.

Creative Placemaking

MOST staff identified models in the Upstate Medical University Life Sciences exhibit as a key area where improvements in representation could be made.

“Our main objective with this project was to better fulfill our core values by making sure that the models and images in our exhibits reflect the people who visit them,” says Emily Stewart, Ph.D., Senior Director of Education and Curation. “Our community is dynamic and diverse, and our exhibits should be too.”

This led the MOST to Rolling Jr. because his consultancy utilizes the concept of “creative placemaking,” a way of transforming a lived environment so it is accessible, inviting, and representative of the community. “That Life Science exhibit was over 10 years old, and it’s striking that there were no persons of color represented,” Rolling Jr. notes. “Out of all those body parts—none.”

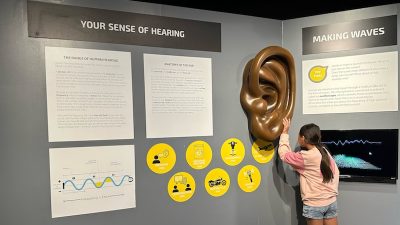

The Upstate exhibit explores the science of human anatomy with larger-than-life body parts, including a heart visitors can walk through, a brain that lights up, as well as a giant ear, nose, lips, and more.

Rolling immediately thought of his former student, connecting the MOST to Meyer-Berthel, due to her materials and preservation skill, unique background, and understanding of inclusivity, a focus of the School of Education.

Perfect Balance

Meyer-Berthel and staff settled on the MOST’s giant ear display to receive the upgrade. “Different ethnicities have different shape ears, certainly, but this anatomy is a little more streamlined across the globe, so an adjustment with paint can change the representation,” she says. “The ear was the clearest choice, because changing the shape of something might actually mean completely rebuilding the object, and that part wasn’t quite in my wheelhouse.”

“Our main objective with this project was to better fulfill our core values by making sure that the models and images in our exhibits reflect the people who visit them.”

Emily Stewart, Ph.D.

But the skill Meyer-Berthel does excel at is combining colors to match skin tone. “No matter the ethnicity, every skin tone includes blue, red, and yellow,” she explains. “You can often tell by looking at a person’s wrist what their undertones are … Finding the perfect blend and balance is the joy.”

Because 28% of Syracuse’s population is African American, the MOST wanted to change the ear to a brown skin tone, but the answer wasn’t as simple as mixing up a batch of paint and applying it.

Other factors Meyer-Berthel had to consider were the museum’s lighting and how this would impact the hue, and how well the paint would hold up to being touched. “The beauty of this exhibit is being able to touch it,” she says, noting, too, that the paint needed to adhere to the material already coating the ear, the composition of which she and the MOST did not know.

After testing samples under the museum’s warm lighting, Meyer-Berthel first cleaned the existing model, using a micro sanding product to help her paint layer adhere. She chose acrylic paints, because she finds these to be the most versatile, and utilized Golden Artist Colors, a New Berlin, NY-based manufacturer of professional artist paints best known for its acrylics, where she also worked as a commercial applications specialist for three years.

“While house paint is wonderful for painting a house, it’s not going to be good for a museum because it has too many fillers in it, like chalk,” Meyer-Berthel explains. “For a museum model, a piece that needs to be so brilliantly colored, you don’t want much in it besides pigment and resin.”

Lastly, Meyer-Berthel coated the paint with a sealant because of how much the ear is touched, protecting it from absorbing oils and dirt from hands.

“We are so thrilled with the work she has done,” says Stewart. “Her thoughtful consideration and expertise helped us to identify the right paint colors, finishes, and techniques to give our older anatomical model a new life.”

By Ashley Kang ’04, G’11 (a proud alumna of the M.S. in Higher Education program)

Learn more about the master’s degree in Arts Education (pre-K-Grade 12), or contact SOE Graduate Admissions at soeadmissions@syr.edu.