Fermentation is something Syracuse University School of Education Professor Michael Gill thinks deeply about. The process is the subject of his latest research and has inspired a recent project to explore family and cultural connections to recipes handed down through the generations and across nations.

Fermentation is something Syracuse University School of Education Professor Michael Gill thinks deeply about. The process is the subject of his latest research and has inspired a recent project to explore family and cultural connections to recipes handed down through the generations and across nations.

The project—Fermenting Stories: Exploring Ancestry, Embodiment, and Place—kicked off in February 2024 thanks to an Engaged Communities Mini-Grant by the College of Arts and Sciences. The funding allowed Gill to offer five workshops in partnership with the local Brady Farm to explore how various communities that call Syracuse home use food fermentation as a culture-making practice.

Workshops have explored recipes from kimchi to yogurt and included accounts by each instructor on their family connection to the fermentation process.

For week four—offered on April 14, 2024—Valerie Khaloo led a group of eight participants through the steps of her grandmother’s zasar (achard) recipe, a popular Mauritian condiment of pickled vegetables eaten on the Indian Ocean island that her family hails from.

Khaloo says she had to test the recipe multiple times prior to leading the class because her grandmother never provided measurements for each ingredient. The process to craft a recipe others could understand—one based on exactness and not her memory of how it should taste –helped her remember her grandmother, who recently passed away.

“Every time I make zasar, I see my grandmother doing it in front of me and I feel closer to her,” says Kahloo. Her grandmother made huge batches of the dish, bringing the whole family together. Khaloo recalls fondly how her family would bond over zasar, extended family members arriving at her house with up to five empty jars to fill.

Gill says he became interested in fermentation at an early age by helping to brew beer with his father and older brother. Later, he tried—unsuccessfully, he says—to make sourdough bread and then vegan kimchi. Then, from the fall of 2018 to spring of 2019, he spent a year on research leave in South Korea, the land of all things fermented.

When Gill returned to Syracuse, he began to use the process as a metaphor for his graduate students. “We talked about the act of fermentation as a metaphor for how we think about research, as something we could slow down, or sort of let the magic or the microbes take over,” he explains, adding that he even assigned his students a fermentation project. “We want to create the right environment and make sure the bacteria is gone, that it has the right amount of salt—or whatever it might be—to allow the ferment to happen.”

Stories from each workshop held during winter/spring 2024 will be archived publicly on a website that is in development. Some accounts, explains Gill, might make their way into a book project that further explores how fermentation serves as a way to preserve one’s culture.

“Preserve” and “culture”—there’s that metaphor again!

How to Make Zasar: A Photo Essay & Recipe

Unpeeled carrots, chopped into very thin strips or sliced with a mandolin, are prepared to be added with the raw green beans, cabbage, and onion. Zasar is one of the most popular condiments eaten on the island of Mauritius, located in the Indian Ocean, just east of Madagascar. Mauritian food is a fusion of tastes from India to Africa.

Zasar is primarily a mix of green cabbage, carrots, and green beans. Instructor Valerie Khaloo says back in Mauritius she would leave the chopped vegetables outside to dry before heating. “They’d sit in the sun for a day, but here … I don’t know if we even have seven hours of sunlight,” she says with a laugh. Instead, she advised participants to pat all the vegetables dry with a paper towel before warming.

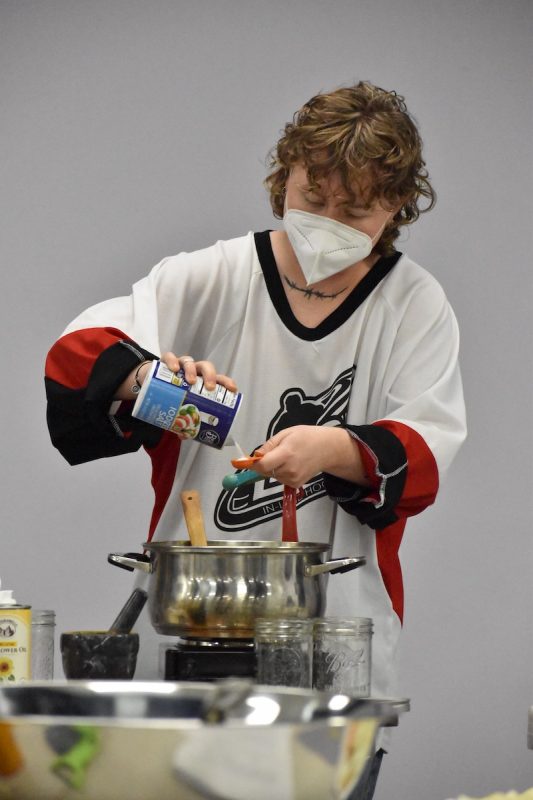

Avalon Gupta VerWiebe G’22, a food studies graduate, roughly chops ginger. Both ginger and apples are the last two ingredients added to the warmed Zasar mixture.

Spices for the Zasar include brown mustard seeds and turmeric powder. The two are ground together using a mortar and pestle until the seeds are coarse. Then, white vinegar is gradually added until the consistency resembles a moist paste. The ideal consistency, Khaloo says, is like creamy peanut butter: “not in-the-fridge peanut butter.”

Khaloo tells participants the best oil to use is sunflower oil, “but the heatness is debatable” because when asked her mother’s advice, she was told to “make the burner warm but not enough to cook or so it gets hot.”

Once the oil warms, add the onions first and then the two cups of mixed vegetables with three smashed garlic cloves. You only want to warm the mixture and not cook, Khaloo believes, because if the mixture gets too hot, it can become bitter.

After warming the vegetables, add about two teaspoons of the spice mix and wait until the vegetables become fragrant. Add the white vinegar after all is warmed through.

Once warmed through, scoop into storage jars, but leave open for a bit to start the fermentation process.

The Zasar mix should be left open for a bit to kickstart the fermentation process. Once sealed, leave the jar at room temperature for one to two days and then refrigerate.

Instructor Valerie Khaloo helps Syracuse resident West Brimmage make a batch of zasar. Professor Michael Gill can be seen in the background.

Brimmage measures salt to add to their warmed vegetables. Under-salting, explains Brady Farm Coordinator Jessi Lyons, will prevent fermentation.

Khaloo guides Syracuse resident Kaija Dockter on what ingredients to warm first.

Zasar is typically eaten with curry, basmati rice, or lentils and other beans. Khaloo says it’s a versatile condiment and is great mixed with pasta, on salads or sandwiches, or just straight out of the jar. She also explains that zasar is good for digestive health, while the ayurveda sunflower oil is warming, and both the turmeric and mustard seeds are anti-inflammatory.

Text by Ashley Kang ’04, G’11 (a proud alumna of the M.S. in Higher Education program)

Photos by Angelina Grevi. Grevi is an incoming S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications freshman. She is a recent graduate of the Syracuse Journalism Lab, which aims to inspire talented high school students from Syracuse’s underrepresented communities to pursue careers in journalism.