When Lilly Thomann ’15, G’16 was an undergraduate at Syracuse University, she seemed to have it all: grades, talent, an appealing presence, popularity. “On the outside, I had it together,” she says.

Indeed, Thomann, who hails from affluent West Caldwell, N.J., hasn’t longed for the niceties of life. The fact that she is an accomplished painter, a versatile athlete with designs on competitive weightlifting and a conscientious student has endeared her to peers and adults alike.

Indeed, Thomann, who hails from affluent West Caldwell, N.J., hasn’t longed for the niceties of life. The fact that she is an accomplished painter, a versatile athlete with designs on competitive weightlifting and a conscientious student has endeared her to peers and adults alike.

But nothing could shake the dark clouds of depression. They loomed over Thomann’s childhood and followed her to Syracuse, where she jointly enrolled in the College of Visual and Performing Arts and the School of Education, earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees in art education.

“At the end of my freshman year, I was depressed and suicidal and ready to transfer out of here,” says Thomann, with a grimace. “I got treatment, but it was short-lived. By the time I was a senior, my depression had grown 10-fold. I hated myself, and couldn’t be left alone. I needed help.”

Thomann is one of more than 25 million Americans suffering from depression. She also struggles with poor body image—something that began in second grade, when Thomann realized she was “bigger” than everybody else. Then it got worse.

Two years later, a “friend” told Thomann her thighs were fat. In seventh grade, she was called a “giant,” and promptly took up dieting. In high school, Thomann’s volleyball coach denigrated her for not having the “correct body type” for the game.

“I eventually became a statistic—one of 24 million people in the United States with an eating disorder,” says Thomann, who, by high school graduation, had shed 70 pounds, lost her hair and menstrual cycle, and experienced anxiety attacks on a daily basis. “By losing weight, I had gained everything I wanted: a great body. I was miserable.”

Today, Thomann, 22, says she is in a much better place, thanks, in part, to the unconditional support of her family. She recalls the end of freshman year when things got so bad that her mom stayed with her for more than a month. “I probably wouldn’t have finished my first year of college, if it weren’t for her,” Thomann says candidly. “The same goes for my dad, who doesn’t make me feel like I need to be perfect.”

A straight-A student, Thomann also remembers her dad warning her about becoming obsessed with grades. “He said it was okay to get a ‘B’ once in a while, if it meant I would be less anxious,” she continues. “My dad gave me permission to have fun. No one ever said that to me before.”

A straight-A student, Thomann also remembers her dad warning her about becoming obsessed with grades. “He said it was okay to get a ‘B’ once in a while, if it meant I would be less anxious,” she continues. “My dad gave me permission to have fun. No one ever said that to me before.”

Mom and Dad must have been on to something because Thomann has blossomed into a successful young professional. Case in point: This spring, she was hired as a visual arts teacher at Manlius Pebble Hill School, a prestigious independent college preparatory school.

“It wasn’t until my senior year of college that I realized I had a beautiful body and should treat it with respect,” says Thomann, fingering a strand of brown, wavy hair. “All of us deal with issues of identity, regardless of age, race, class, and gender. We’re all products of our environment. I certainly am of mine.”

For as long as she can remember, Thomann has been passionate about art and athletics—two seemingly different worlds that she has navigated with relative ease.

Her passion transferred to the classroom. As an undergraduate, Thomann excelled in the Renée Crown University Honors Program, an all-University program in the College of Arts and Sciences. It was the prospect of doing a Capstone project, in conjunction with VPA’s School of Art, that convinced her to choose Syracuse over Purdue University.

Samuel Gorovitz, professor of philosophy and former dean of A&S, was one of Thomann’s Honors teachers. “As a student, Lilly was really superb, in written work, examinations and participation in vitally important class discussions,” he remembers. “She was one of only two or three in my course [“Beautiful Minds”] who were unambiguously and clearly solid high-A performers all the way through. She was—and is—as kind as she is smart.”

In Honors, Thomann succeeded through hard work. Her Capstone project, “Developing Self-Love, Self-Worth, and Body Image Acceptance Through the Arts,” drew on her twin interests in art and body dysmorphia, a psychiatric disorder in which one is obsessed with one’s own perceived defects or flaws in appearance.

In Honors, Thomann succeeded through hard work. Her Capstone project, “Developing Self-Love, Self-Worth, and Body Image Acceptance Through the Arts,” drew on her twin interests in art and body dysmorphia, a psychiatric disorder in which one is obsessed with one’s own perceived defects or flaws in appearance.

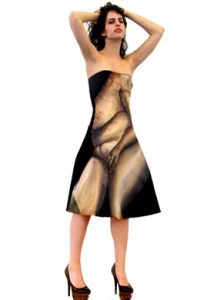

Thomann took a critical and somewhat comical look at dysmorphia, creating a series of photographs that showed models in clothing on which corresponding, life-sized body parts had been painted. The size of the body part, however, was in sharp contrast to the size of the clothing.

“It’s human nature to obsess over how we look and how we think others see us. These concerns shape our understanding of body image,” says Thomann, who blames popular media for exacerbating many such misconceptions. “My capstone project considered the obsessions we have about ourselves. The permanency of the acrylic paint represented the overwhelming concern, confusion and self-doubt we have about how we look.”

Thomann’s capstone was such a success at Syracuse that she submitted a presentation proposal on it to the 2016 National Art Education Association (NAEA) National Conference in Chicago. In March, Thomann—two months’ shy of graduation—found herself addressing the world’s largest art education convention.

Was she nervous? Yes.

Did she nail it? Of course.

“I became a teacher for one reason: to change lives and help adolescents through a really tough time,” says Thomann, adding that she was 19 when she started addressing body image in her art. “As I told everyone at the NAEA, the art room is an excellent platform to teach self-acceptance and love, but it shouldn’t end there. We, as educators and mentors, need to be teaching it across all subject areas.”

Thomann is incredulous about the fact that most schools address sexual health and substance abuse, but do nothing about self-worth. She cites a recent article by plus-size fashion and beauty blogger Georgina Grogan, who writes that people with even “relatively minor body concerns” are prone to associated health-risk behaviors. “Not everyone who struggles with poor body image develops a diagnosable eating or mental disorder,” Thomann says. “But there are so many behaviors—exercise avoidance, use of anabolic steroids, unhealthy eating, a desire for cosmetic surgery, and drinking and smoking—that fuel self-loathing. Many of these patterns, regardless of gender, begin at an early age.”

How can these patterns be undone? Thomann thinks part of the answer—at least in the K-12 classroom—may be found in TED Talks, particularly the ones by Victoria’s Secret model Cameron Russell and contemporary artist Janine Antoni. “TED Talks are great because they’re short, focused and free,” says Thomann, who has used them in a variety of educational settings. “Best of all, they foster a dialogue about the presence of media in society, our exposure to contemporary artists and multiple modes of art making.”

Thomann says TED Talks are no substitute, however, for the creative process. She is particularly keen about getting students to create self-portraits because the process encourages self-examination and expression. “For me, self-portraits are a reflection of my vulnerability. They’re a way to explore my humanity, personality, strengths and weaknesses,” says Thomann, whose own portraits are laced with symbolism, images and ideas. “I try to leave things up to the viewer’s imagination.”

Thomann says TED Talks are no substitute, however, for the creative process. She is particularly keen about getting students to create self-portraits because the process encourages self-examination and expression. “For me, self-portraits are a reflection of my vulnerability. They’re a way to explore my humanity, personality, strengths and weaknesses,” says Thomann, whose own portraits are laced with symbolism, images and ideas. “I try to leave things up to the viewer’s imagination.”

That Thomann is a proponent of process over product seems to make her popular with her own students and her peers at Syracuse. She talks about working with a first-grader who was so lacking in confidence that she couldn’t do anything by herself. When Thomann asked her to draw a cloud, the student refused, explaining that her cloud, like everything else in her life, was “not perfect.”

“Who told you that you had to be perfect?” Thomann asked.

“My mom, my dad, my siblings, teachers, friends,” the 7-year-old replied.

“You know, if every cloud looked the same, the sky would be really boring,” Thomann countered.

In tears, the student sat down and reluctantly began to draw. And draw. “She never asked me to draw anything for her again,” Thomann says with a smile. “The only time she came up to me, after that, was to show me what she had made, with pride.”

It’s this interpersonal connection, Thomann says, that keeps her going—in the classroom, the art studio and the gym. Probably no one looms larger in the last category than Dan Goldberg, Thomann’s coach at CrossFit Syracuse, near campus. He recalls meeting her in 2013, when she was a “quiet young lady and clearly not comfortable in a gym.” Goldberg says that, thanks to a gift-membership from Thomann’s grandmother, she has blossomed into an “average professional athlete with professional-level talent.”

“She starts workouts fast, reaches a certain level of physical pain, and decides to stay there, whereas most beginners retreat,” says Goldberg, praising Thomann’s “100-percent” work ethic and proclivity for weightlifting. “CrossFit has shown Lilly that she is incredibly strong and powerful. When she lifts during class, everyone stops to watch because it’s such a beautiful thing to see.”

Whether holding a barbell or a paintbrush, Thomann is most proud of her hands. They’re the one body part that never seems to fail her. (Case in point: Thomann’s most beloved artworks are “Comfort” and “Affection,” which she painted in 2014 and feature close-up, florid exaggerations of her palms and fingers.) “I have storyteller hands,” Thomann says half-jokingly. “Every cut, scrape and bruise tells a story.”

Goldberg says Thomann’s hands also help with timing, position and accuracy, all the things crucial to weightlifting. “Lilly is well on her way to achieving something in the sport,” he says. “I’m so proud of her.”

Sharif Bey, an associate professor of art education in VPA and the School of Education, echoes these sentiments, also drawing on the storyteller analogy. “Her struggles, vulnerabilities and triumphs have become points of departure for telling intriguing, entertaining and powerful stories,” he says, adding that her progression from shy student to confident educator has been dramatic.

“She emerged from the chrysalis not as an elegant butterfly, but as a fierce eagle, taking to the sky with her newfound mission [of self-love],” Bey says. “Most budding teachers aspire to make a difference, but they don’t always discover their sense of purpose so soon. She has learned the importance of community and self-love, and understands how to use art to restore and cultivate.”

As Thomann transitions from college to the workplace, she reminds herself that a happy life is not a perfect life. She says she still struggles with the “fog of depression” and that some days are better than others. But thanks, in part, to people she has met at Syracuse, Thomann is less likely to relapse.

“There was a time, during college, when I had a friend who would stay up with me at night, so I wouldn’t hurt myself,” she says, with a trace of emotion. “I’ve gone from being my own worst enemy to being my own best friend. Syracuse helped with that, showing me how to use art to think about my body in a new way. I’m not perfect, and that’s good enough for me.”

Original story by Robert Eslin