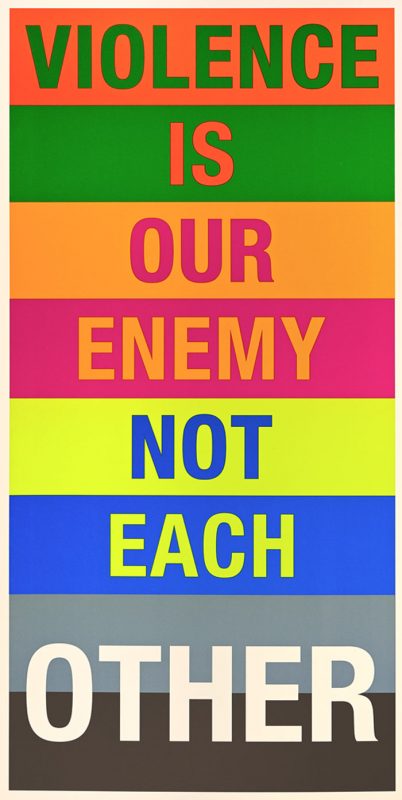

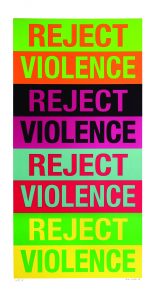

If you have traveled the streets of New York City during the month of September, it’s likely that you have seen Diana Wege’s artwork. The bold block letters and lines of contrasting colors on her series of Reject Violence prints may have confronted you with Wege’s mission of ending violence in our lifetime.

If you have traveled the streets of New York City during the month of September, it’s likely that you have seen Diana Wege’s artwork. The bold block letters and lines of contrasting colors on her series of Reject Violence prints may have confronted you with Wege’s mission of ending violence in our lifetime.

A recent print proclaims, VIOLENCE/IS/OUR/ENEMY/NOT/EACH/OTHER.

“I think art demonstrates the priorities of a society,” says Wege ’76, a member of the School of Education’s Board of Visitors who earned a B.F.A. with an independent study concentration on painting and Japan studies. The prints have appeared on NYC transportation kiosks during the month of September for International Peace Month, on and off for the last several years, and will appear again in April 2020 with a plea to end violence against the environment.

“I loved drawing and colors at an early age,” she remembers. When she was 7, “a nun recognized my advanced artistic ability and told me that it was a gift from God. I asked her what she meant, and she said that I must take it seriously.”

Wege has become a conceptual artist whose work emphasizes an end to violence, especially in schools, and explores the connection between the environment and social justice.

“The United States is one of the most violent cultures on Earth. So much of art reflects more and more violence as artists compete to create the most violent imagery,” she says. “I’m trying to change our priorities back to gratitude for earth, air and water, and ability to solve conflicts without force, through a culture of dialogue.”

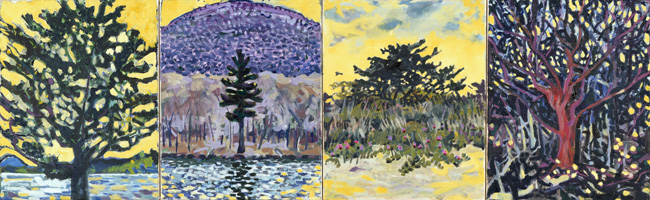

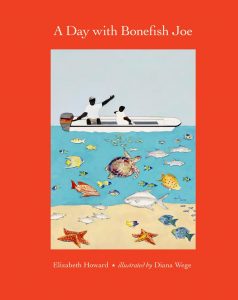

Wege’s artwork ranges from prints to large panoramic landscapes to a site-specific installation for choir and chamber orchestra to illustrations for a children’s book, A Day with Bonefish Joe, by Elizabeth Howard, about an adventurous girl’s day at sea with a fishing guide in the Bahamas. From 1996 to 1998, she visited 24 parks and Nature Conservancy properties across the United States, then painted 18 landscapes for her book, Land America Leaves Wild, published in 2000.

“I enjoy the challenge of mastering different artistic practices,” she says. “With each endeavor I address very large societal problems and attempt to solve them. I’ve lived a blessed life. I want everyone to feel that way.”

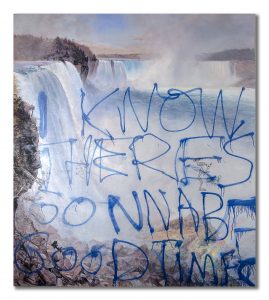

Her anti-violence prints have been shown at Swab Barcelona’s contemporary art fair, Art Fair Tokyo and Art New York. In 2012, she painted two panoramic landscapes nearly 9 feet by 8 feet each in the style of Frederic E. Church’s Niagara Falls from the American Side. One, Altered Copy of Niagara Falls from the American Side with Graffiti, was the cover art for the first issue of River Rail, a biannual publication focused on the intersection of art, activism and environmentalism.

Earlier this spring one of these paintings was installed on a Cortland Alley wall in Tribeca and 8 months later it remains, open to the elements and the chance of graffiti, as Wege intended. She likened that risky exposure to the threats facing the American landscape. She says, “I don’t feel it is “finished” yet.”

The paintings also form the basis for her site-specific installation, a performance piece called Earth Requiem, which she conceives as a warning about the effects of climate change and pollution on the planet’s future. Wege is working on 14 paintings to form a sacred space like Stonehenge or Stations of the Cross. The audience will face an altar that will hold one of four editions of a new handmade book, EARTH (the First and Last Testaments), gathering eight sacred texts in the public domain and 10 books of environmental literature. She has commissioned four composers to create 20-minute movements for orchestra and choir, to be sung in the spring for Easter, Passover and Earth Day or in September for International Peace Day.

She hopes for a performance in 2021.

Wege’s efforts at conflict resolution began after her divorce in 1995, when she said she realized neither she nor her ex-husband could talk through a problem assertively. “I thought of getting conflict resolution taught in schools to ensure that not only would my children be able to talk through a conflict but so would anyone they chose as their spouse,” she says.

The result was the Crusade Foundation, formed in 1998, which gave grants for anti-bullying programs to schools in Connecticut. After the shootings at Columbine High School in 1999, the organization created conflict resolution training programs across Connecticut. Crusade was an anagram of the first letters of Conflict Resolution Designed for Educators in the United States.

A decade passed, and violence didn’t abate.

“I was sensing that the rate of violence was escalating,” she says. “So as a basic first attempt to discourage a person that might be thinking of doing violence, I bought ad space and created a print that encouraged finding other options.”

She had read The Stick-Up Kids by Randol Contreras, a 2012 book “about boys growing up in the South Bronx and how much violence they used to steal from drug dealers. How could I live in the same city with them without trying in some way to change their lives?’’ Wege asks.

The first Reject Violence prints appeared in 2013. “They were a knee-jerk, probably feeble, attempt to lessen violence, but they were out on the streets for people of all ages to see,” she says.

In November 2013 Wege launched We Oppose Violence Everywhere Now (WOVEN) as its board chair. A nonprofit organization based in New York City, WOVEN says it “aspires to end violence in our lifetime.” Using its digital platform, urban print art and grassroots organizing, WOVEN aims for collaborative efforts to create solutions to end violence. It has provided grants to local, national and international organizations and created Nurturing Inclusive Community Environment (NICE), a program to implement community-building circles and conflict resolution practices in high schools.

Wege credits the SOE’s Office of Professional Research and Development for assistance in developing and evaluating NICE. Its director, Research Professor Scott Shablak, and Research Coordinator Mary Welker “have helped us so much.”

Wege credits the SOE’s Office of Professional Research and Development for assistance in developing and evaluating NICE. Its director, Research Professor Scott Shablak, and Research Coordinator Mary Welker “have helped us so much.”

NICE is in the third year of a pilot program with the East Ramapo School District, where, Wege says, the suspension rate fell 59 percent in the second year and the graduation rate has gone up more than 10 percent.

“Our goal is to create nurturing environments in all public schools where kids of all abilities will feel welcome and empathetic and assertive,” she says. “When students make mistakes, they will be guided in learning from them, not suffer isolation and punishment.”

The welfare of all students, nationwide, is her priority. The New York Times published a letter from her in October reacting to an article about a Des Moines, Iowa, football team that can’t compete with richer suburban schools. She called for the federal government to pay for school education.

“Continuing to have local school districts pay for our children so unequally is a crime. Every school should have well-funded athletics, art, music, social workers, counselors and a nurturing staff,” she wrote.

Wege concluded with a goal all educators share: “The federal government could proudly raise the bar for all of its schools and reduce failing schools in America to an oxymoron.”